Man, it feels good to be making stuff again.

This is another dish from the book I’ve been eyeballing since day 1 with it; it’s so pretty, and has that ‘weirdness’ factor that I like so much about this kind of cooking. It was appealing at this particular time because it doesn’t involve a lot of expensive kitchen gadgetry (or, at least, involves gadgetry I already own). At first blush I thought I could bang it out in a weekend, but there are a few sentences in the recipe I’d overlooked, like “dehydrate this for 24 hours” or “let this sit overnight”, that I only discovered once I got partway into the recipe. That, coupled with a pretty notable derailing, has taken this from what I thought would be a simple way to get going again into something much more involved.

Rose petals were easy; we have some nice rose bushes growing in the front yard of our new apartment.

Before I get too far into what actually happened, I’ll say what I EXPECTED to happen. This thing visually looks a little like a ragged, large Listerene breath strip. I expected it to have the same ‘feel’ in the mouth; a very short ‘crispy’ moment followed by a quick dissolve and a vague sense of a series of flavors. The main body of the Transparency is derived from raspberries, with candied rose petals and sprinkled powdered yogurt atop it. Our friends in SF get together on Wednesday nights to watch “So You Think You Can Dance”, a show I’m more interested in than I usually admit, and I thought it’d be fun to try to roll up with some Raspberry Transparency for dessert, to really enhance the finer undertones of our usual fare of chinese takeout and watery beer. So even with the longer steps involved in the recipe, I figured if I started it on Saturday, I could finish it by Wednesday.

After candying the rose petals, they’re dehydrated to crisp them up.

Unfortunately it didn’t really work out exactly that way. My first run through making it, I got hung up on one of the final steps, where I’m supposed to dehydrate something like a raspberry fruit roll-up into something that’s crispy like a potato chip. No amount of increasing dehydration temperatures or times helped this though–the raspberry sheets just stayed right at the leathery consistency they’d started at. So I backtracked a step: making the fruit roll-up stuff involves a process similar to that of making pineapple glass. I was supposed to smear some liquid onto a sheet of acetate to get it as thinly-spread as possible. Doing this took me several tries for that pineapple recipe as well, and the book is sparse on details about how big a sheet of acetate to use, how much liquid to pour onto it, etc, so ‘as thin as possible’ is a bit vague. I figured my roll-ups weren’t crisping up because they were just too thick, so I tried again with the intent of literally spreading the raspberry liquid mixture out as thin and faint as it would possibly go on the acetate sheets. Surface tension of the liquid kept a threshold to how thin I could get it, but even doing this failed; when I tried a second time to crisp these sheets up, nothing happened.

Raspberry pulp draining through a cheese cloth-lined chinois

Raspberry pulp draining through a cheese cloth-lined chinois

So I went back to have another look at the recipe, and noticed something: the type of pectin the recipe calls for was different than what I’d used. In picking up momentum on this project, I’ve found that a lot of these recipes are actually more forgiving than I might have expected. An extra gram or two here and there for this and that still yields something that’s well within the ballpark of the final goal. I thought this might have been the case here too. When I figured out I’d used the wrong ingredient, I actually got a little excited. I’d figured things were wrong simply because I’d rushed and was a tad sloppy, but use of the wrong ingredient not only made me slow down but also afforded me a chance to learn something subtle.

Raspberry juice

Raspberry juice

The book has a section describing the various unusual ingredients it tends to use, and there’s a small section about pectin. It specifically mentions what seems to be 3 types of pectin: High-methoxy yellow pectin (‘HM’ pectin – what you generally find in supermarkets), Low-methoxy pectin (‘LM’ pectin), and ‘NH’ pectin, which is thermo-reversible (it doesn’t explain what ‘NH’ means). Reading through this the first time was a bit overwhelming, and I didn’t retain much of this information. I was basically just skimming to try to assemble a master list of ingredients I’d need to order. When I was investigating the purchase of these ingredients, I got an email from one place that had this sentence: “If you want to get the apple LM Pectin (NH), we have it too.” I asked for clarification on this, and was told that ‘LM’ pectin is ‘NH’ pectin.

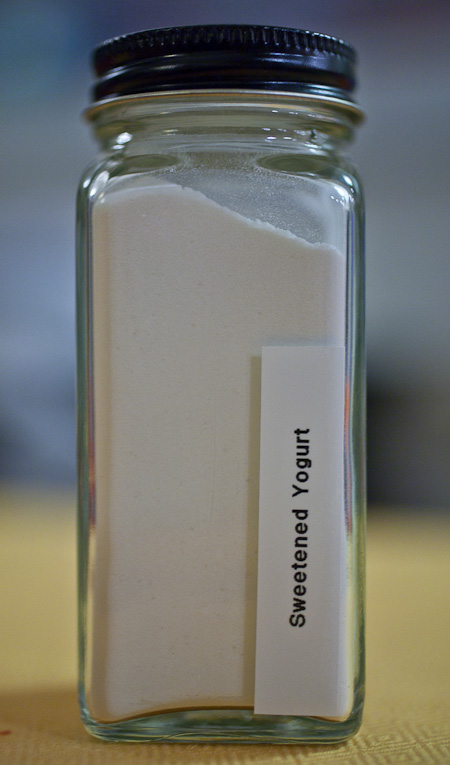

I used Adria’s ‘Yopol’ Texturas product for the yogurt sprinkling. It’s very tangy and ‘yogurty’; I dig it.

So I bought a bag of yellow (‘HM’) pectin ($31) and a bag of ‘LM’ pectin ($17) and called it a day, thinking that the cheap ‘LM’ pectin would be what I needed to use when NH pectin was called for. Incidentally, the website through which I bought the pectins also lists a ‘NH’ pectin that sells for $63, which I skipped getting, thinking that the $17 bag of pectin was the same thing.

The first time through making this recipe, I’d used the yellow pectin by mistake, which is apparently just flat-out wrong. It wasn’t until things weren’t working did I think to notice all this.

All of this reminded me that a ton of thought and consideration has gone into the selection of each ingredient (and quantity) being used in each of these recipes, and I’ve been so focused on moving forward quickly that I’ve overlooked trying to understand why each is used. So I tried to read up a bit on the different types of pectin, and figure out why NH pectin might have been used here. Here’s some of what I found:

Ideas In Food gives a very readable overview of pectin:

http://ideasinfood.typepad.com/ideas_in_food/2008/02/a-brief-overvie.html

Something interesting in that above article: “LM Pectins are thermally-irreversible”. This recipe involves a few steps where the raspberry mixture is gelled, remelted, and gelled again in different forms, so I suppose this is why LM pectin wouldn’t be a good choice (this flimsy rationale doesn’t address why thermoreversibility is important to the creation of this dish to begin with, though). But, the comments in this article:

http://www.eatfoo.com/archives/2008/03/recipe_soft_chocolate.php

mention this interesting bit: “…a high methoxy pectin…in order for it to gel, it needs fruit that is already high in pectin, a low ph environment and a high rate of dissolved solids”. I think raspberries are low in pectin and higher in acidity than other fruits, which might suggest that HM pectin, which ostensibly IS thermally-irreversible (?), wouldn’t work. I also think NH pectin might be a type of LM pectin, with some extra bells and whistles that allow it to behave like HM pectin maybe?

A lot of this reasoning is really just conjecture though. The Alinea book uses dozens of hydrocolloids, and I really have no idea why pectin was the one chosen for this dish, nor why NH pectin is the only type that makes this dish work. I emailed the Alinea Mosaic forum to put forward this question, to get clarification on the various types of pectin and why this particular one was chosen, but haven’t yet gotten an answer. It makes me feel itchy to know that I don’t fully understand this.

What I do understand, though, is that NH pectin is absolutely imperative for this recipe to work, and that precise amounts of everything are of paramount importance. So I’m thankful that making this has encouraged me to slow down a bit and remind myself why I wanted to do this project to begin with: to learn.

And in the end, I got something well within the ballpark of what I expected; the NH pectin allowed me to dry out the raspberry into paper-thin sheets, that then turned into something kind of like edible acetate. They were crispy until they got moist in my mouth, then sort of turned into something like jam. I came to appreciate rose water in the Granola Envelope recipe, and am avidly a fan of it after tasting it mixed with raspberry here; the two flavors pair extremely well together in a way that’s reminiscent of how potatoes pair with truffles; it’s hard to pick the two apart–it just tastes like ‘super-raspberry deliciousness’. The yogurt powder’s tang adds a nice front-weighted flavor when you first bite into this, which is chased up quickly by the raspberry. So far I’ve shared some with Sarah’s family, who’s in town visiting for the week, and my dehydrator is cranking out another batch to share with friends over the coming days.