So here we are, five years to the day from when this project was born. Everyone ready?

Let’s begin.

“Icefish” are a family of fish found primarily in freshwater areas of Southeast Asia. Sometimes also referred to as “glassfish” or “noodlefish”, icefish are small, with translucent bodies. They are believed to be “neotenic”. meaning some characteristics of baby icefish are retained through adulthood. Among the most interesting of these are lack of development of scales or bones–adult icefish have no exterior scales and are completely cartilaginous. This is interesting to us because it means if we drop a fresh icefish into hot oil, it puffs…sort of like a tiny fishy pork rind.

It’s perhaps unsurprising for me to suggest that icefish are not straightforward to find in markets, especially if one wants to find them fresh. I checked a few Asian markets around the East Bay and in the city, but the closest I could find was a box of small, ambiguously-labeled whitefish in the freezer section of a 99 Ranch. Tokyo Fish Market in Berkeley hadn’t heard of icefish, and when I pressed them to check their purveyor in Japan to see if they could import some, they reported back that they couldn’t.

Undeterred, I emailed good old reliable Carl at True World Foods. Carl has proven extremely helpful in the past in my search for Ayu, Sea Grapes, and Tosaka, so I figured he’d be able to track down icefish easily enough. After a few days, he responded “Sure, no problem, this product is called ‘shirasu’ in Japan. We can get this for you.”

This sounded great, except for one thing: I knew Carl was wrong.

I learned about shirasu quite inadvertently when trying to track down Tatami Iwashi last year: shirasu translates to “whitebait”, a collective term referring to the fry (babies) of a number of small fish. While icefish can technically be considered whitebait, I knew the term offered by Carl was a generic one, and that in practice Japanese shirasu are typically anchovies or sardines. I had a gnawing feeling icefish were something different.

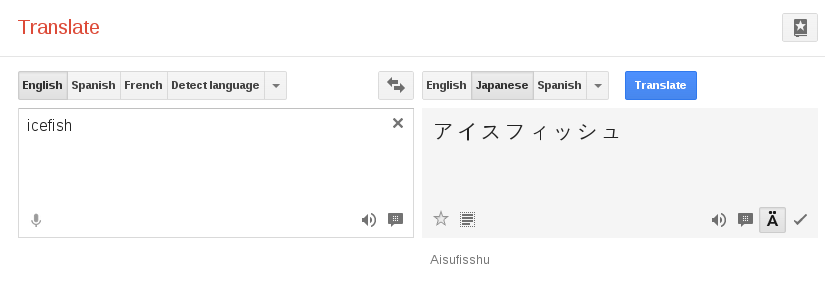

I reasoned that there was likely a Japanese term for icefish, and that figuring it out might help Carl and I track down the correct ingredient. To do this, I turned to Google Translate to convert the English word “icefish” into Japanese characters.

When I copied the above characters back to a Google search page, I was presented with heaps of results, all in Japanese. I switched over to Google’s Image search, thinking that if I’d properly-translated the phrase, I’d see photos of icefish resembling those in the Alinea cookbook itself. Instead, I found photos of much larger fish that are also known as “icefish” but that thrive mostly on the ocean floor in Antarctica. Not what I wanted.

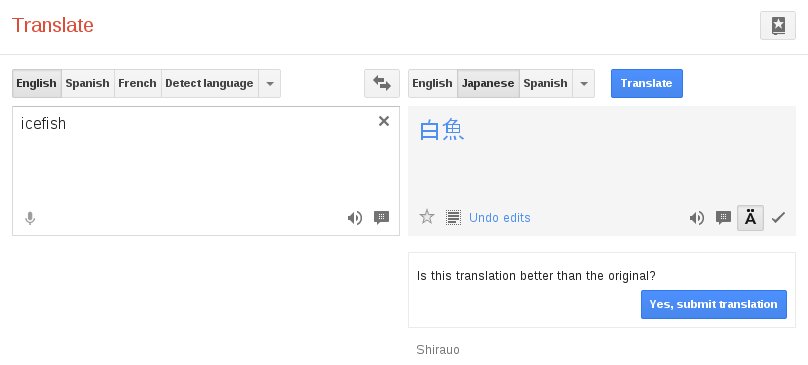

I went back to Google Translate, and noticed that when I hovered over the Japanese characters, I was offered the option to see other translations of “icefish”.

Copy-pasting this other translation into Google Image Search turned up hundreds of photos of exactly what I was looking for; tiny, ghost-like fish native to Japan. Curious about this discrepancy, I did a little bit of research into the Japanese language. The difference, I found, is due to the multiple scripts that comprise the Japanese writing system. In the first case, I was looking at katakana characters; these characters are used, among other things, for transliteration of foreign words and phrases. So, the first translation result had been for the Japanese translation of the English word “icefish”.

In the second translation, Google Translate had offered kanji characters; these characters are typically used to write native Japanese words or phrases. In the case of this recipe, “icefish” is actually the English translation of the Japanese phrase “白魚”.

Google Translate also offered the rōmaji form of the phrase; rōmaji refers to the application of Latin script to the Japanese language. When you order “hamachi” or “shiro maguro” in a sushi restaurant, you’re invoking the rōmaji forms of the Japanese names of these fish. Likewise, “shirasu” is the rōmaji form of the Japanese phrase for “whitebait”.

We can see above, then, that Google Translate is suggesting the rōmaji form of the Japanese term for “icefish” is shirauo. To confirm I’d found the right phrase, I did one last Google search for shirauo; the results are predominantly in English, and invariably describe this small fish I was in search of.

I wrote Carl back, confident in my assertion that I didn’t need to place an order for shirasu, but instead needed a few containers of shirauo. His response came a day later: “We can’t source this. Just use shirasu, it will taste the same.”

I was crestfallen at Carl’s dismissal and unwillingness to help, especially given the effort I’d put into understanding exactly what ingredient I needed. Unsure how to proceed, I took to Twitter, asking Alinea if they had advice for where I could source shirauo. There was no response offered.

I sat frustrated for a day or two, then had an idea. Chef David Barzelay has been an encouraging and insightful friend for a sizable duration of this project, offering comments and emailing me about various things for years. At one point a while back, he generously mentioned that if I ever needed help sourcing an odd ingredient to let him know, as his own Lazy Bear project frequently puts him in the path of many interesting products. Because I’m stubborn and am also loathe to be an imposition, I had never taken him up on this offer. But, confronted with the prospect of substituting the main ingredient in this final dish, I decided to phone a friend.

His response was swift and awesome. “Try calling Glenn down at International Marine Products south of the city; he’s great and he cares a lot about good product.” He forwarded me an email address and a phone number, and I immediately sent a note to his contact.

Sure enough, Glenn responded within a few hours: “Yes, I can get shirauo; we can bring it in from Tsukiji Market fresh for you. Pick up dates are Tuesdays and Fridays; would you like to place an order?”

You bet your ass I would, Glenn. Also, I could kiss you, Glenn.

I drove down early the next Friday morning to International Marine Products, where I met Glenn and his coworker Mangki, who had imported two small packages of fresh icefish for me the night before. IMP sits south of San Francisco, right near the San Francisco International Airport. It’s little more than a garage brimming with fresh seafood; Glenn explained that IMP has a sister office in Tokyo, and that they specialize in importing rare or hard-to-find seafood for high-end restaurants in the area. “Whatever you need, let me know and we can get it for you,” Glenn assured warmly. Would that I had found Glenn and Mangki years ago, but I’m still thankful for the connection from Chef Barzelay, and look forward to excuses to work with them again.

Icefish in hand, I turned to the rest of the ingredients for the dish. The recipe calls for a multitude of shellfish: littleneck clams, mussels, razor clams, and whelks. The littlenecks and mussels are fairly common in the Bay Area, and whelks (a type of sea snail) can be found with some effort at Asian markets. Razor clams prove to be a confusing product, largely because there are several clams that are often referred to by this name. Pacific razors are a seasonal product in the Bay Area, and are somewhat larger than the longer, thinner razor clam found on the east coast of the U.S. The cookbook does not specify which clam it uses. Lack of availability of Pacific razors at the time I was able to source icefish–coupled with my suspicion that Alinea probably sources Atlantic razors–led me to seek help once again from Browne Trading. I had placed an overnight order for several pounds of Atlantic razors, due to arrive the same day as my icefish. After picking up the icefish and razors, I also darted around to several markets, both in the city and the East Bay, collecting mussels, clams, whelks, and the rest of the produce I’d need to complete the dish.

On arriving home, the first thing I worked on was dehydrating various produce. Among these were fresh horseradish root, onions, cornichons and elephant garlic cloves. Each of these was very thinly-sliced or -slivered, then dehydrated for several hours until they were brittle, light and papery.

As this first round of produce was drying, I worked on a second batch of items, starting with some capers. I rinsed these a few times, then dropped them into hot oil until they were puffed and crispy. These went onto a shelf in my dehydrator that I’d lined with paper towels; I swapped the towels out every so often until the capers were dry and completely fat-free.

I gave the same treatment to some fresh parsley leaves, separating them from their stems and quickly frying them until they puffed, then draining/dehydrating them for several hours on paper towels until they were crisp and beautifully emerald-green.

I also cut some small Yukon Gold potatoes into small egg-shaped ovals, then sliced these into thin chips. I clarified about 2 lbs.of unsalted butter (which yielded about 1 lb. of clarified butter oil), then fried the chips gently in the butter oil until they were very crisp. These were salted, then laid out on a paper towel and dehydrated until shatteringly-crisp. These are by far the most delicious potato chips I’ve ever eaten; the fry in butter gives them a rich, creamy flavor reminiscent of Ritz crackers, which goes delightfully with the light dusting of salt I sprinkled on them. They’re pretty amazing.

While all of this was dehydrating, I pulled some meyer lemons from the freezer that I’d quartered and packed in a mixture of salt and sugar a few months ago. I carefully removed just the outer peel from these, then trimmed the peels into tidy small squares.

Next, I worked on preparing some asparagus in a few different ways. I cut some of the most perfect tips from a bunch, blanching them quickly in salted water and reserving them in a small container. I next picked a few nice-looking stalks and blanched these as well, then carefully trimmed them into thin strips.

The leftover stalks and remaining asparagus were blanched together in a third batch, then blended with some Xanthan to yield Asparagus Coulis.

The final steps involved working with the shellfish. I started by cooking each type of shellfish in a common broth of water, fennel, shallot, and other herbs and aromatics. Once the shells had opened, I removed the meats and trimmed them according to inscrutable Alinea specifications (I’ll conclude this project without knowing if I’ve ever actually done this right; there are no explanatory photos and the instructions are pretty brief), reserving them each on a pad of ice in the fridge.

The remaining shellfish broth was then cooked with cream and an alarming number of thickeners and hydrocolloids. I think I might have used some of almost everything I had; egg yolks, xanthan, ultra-tex 3, agar–the whole gang came to this party. The resulting cream was very thick, without being pasty, sticky, gooey, or snotty though. And it tasted richly of the sea.

I was perplexed at the recipe’s insistence on controlling water with such tenacity until I started plating the dish: nearly every ingredient is presented vertically here, a feat accomplished by a long, fat bead of shellfish custard piped along the diagonal of the plate. This bead serves as a sort of culinary cement, offering a thick footing to all of the light, crisp dehydrated components, as well as the puffed icefish themselves. This is vital, as placing the components is a bit like setting up dominos: if one item tips off balance it can bring down several inches’ worth of other plated ingredients (a lesson I learned the hard way multiple times). All told, I ended up plating this dish about a half-dozen times over two days, taking photos of each as fast as I could before moisture seeped into the bases of the dry ingredients and they began to flop over.

Of course, I didn’t mind this, because it meant getting to taste every dish, the overall experience of which I would call “interesting” though not necessarily “the pinnacle of awesomeness.” A large spoonful of bits of everything tastes just like a lot of stuff; sort of oceany, sort of herby, sort of asparagusy. The shellfish meats are all cold (having been sitting on ice before service), as well as the asparagus and horseradish cream; the dried ingredients are all room temperature. This, I think, leads to a bit of an odd way to deliver these flavors, which I imagine might taste more rich if served warm. But there’s nothing in the recipe about this, so I find the final experience a little lackluster, despite the dish being unarguably quite visually beautiful.

And that, my friends…is that.

Actually, wait. There is one more small thing…

I love your little explanation on Japanese language. Chip and I took a few semesters of Japanese recently and all the different alphabets/writing systems (katakana, hiragana, kanji) are a total kick in the head. Can’t wait to see what comes next.

Recently stumbled upon your blog. As an amateur that’s completed 90% of the TFL recipes, I’m extremely impressed, particularly when you add in the photography and commentary. Killer job. Congrats.

Oh man, thanks Casey! Also, YOU’RE SO CLOSE. That’s awesome; I can sympathize with how that feels for ya.

Huge congratulations!

To do what you did at the level you did it, it’s quite an achievement.

Out of pure selfishness :), I hope you’ll pick up another cooking project.

Regardless of what your future project is, I hope you’ll continue to share your work as you did with your Alinea project. Your pictures are of great inspiration for me.

Good luck!

Cornel