Hi. Last weekend I took a butchery class. If the idea of seeing photos of this seems potentially terrible to you (not a lot of blood and no guts, but a reasonable amount of meat- and bone- cutting), feel free to skip this one. We can still be friends, it’s cool.

Everyone else, please step with me a few safety page-downs this way…

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

⇩

My story begins with the Lamb dish from a few weeks back. This recipe calls for “lamb loin”. Ordering meats from a butcher counter is not something I grew up with; Leitchfield’s primary grocery store is Wal-Mart, and I’ve never seen a butcher counter in there. Ever. As far as I knew, meat grew up inside shrink-wrapped packages of styrofoam, grazing lazily and impossibly on whatever Meat eats, before being picked up by the Meat Stork and flown freshly into my local Wal Mart. Because of this, I’ve never felt confident or knowledgeable ordering from a butcher counter, and in fact find the process a little (shhh) embarrassing and stressful because I know so little about it. What’s the difference between a new york steak and a tenderloin? Why are they priced differently? Which is more awesome? Which is “right”?

When I went to ask for a lamb loin, the thickly-accented butcher at Piedmont Grocery asked if I wanted the tender or the sirloin. “Um. T…the loin?” I stammered.

“You want the whole thing?” he asked.

I think so? I mean, the book says, literally, ‘lamb loin’, so I figure that’s what they want me to buy. I bring home a full lamb loin, trim it down as specified, and end up with a piece of meat that’s maybe 4 times bigger than what the book says I should have. Frustrated with the experience and encouraged by Sarah, I started looking around for some kind of butchery training in the Bay area.

I ended up finding two classes that looked particularly interesting, so I signed up for both. The first of which I had this past weekend at Avedano’s in Bernal Heights. This butchery is owned and operated by three female chefs who opened it as a pet project for themselves during their spare time. One of the owners, Tia, is executive chef at Sociale and was our teacher for the afternoon.

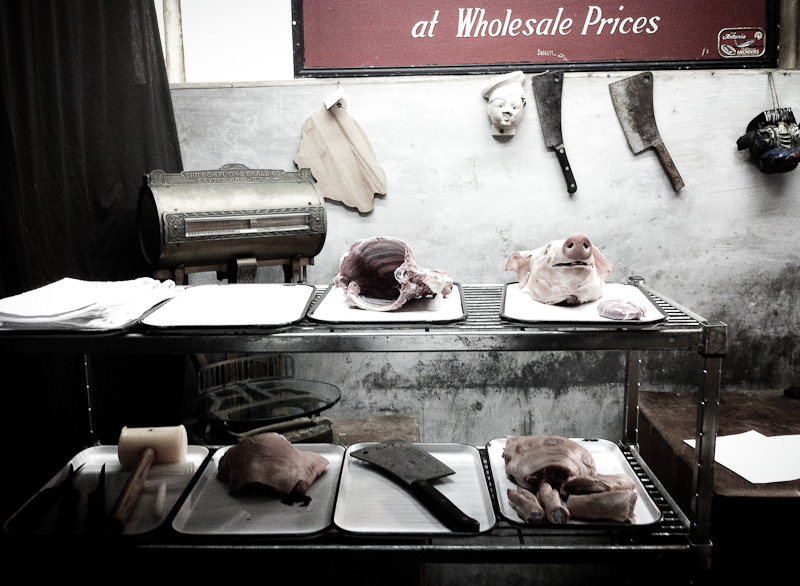

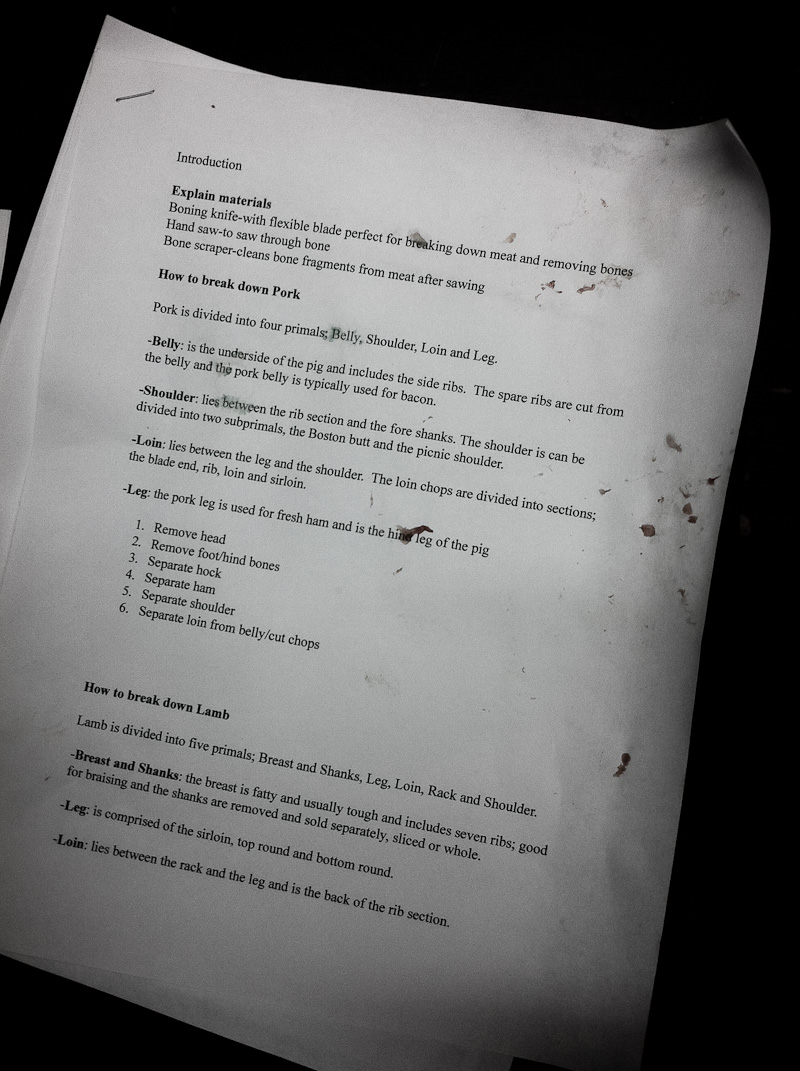

After introducing herself, Tia told us we’d be breaking down two animals during our class; a suckling pig and a lamb. Both animals were of similar size but obviously different structure. The class focused on breaking down the animals into primary cuts (which are larger, generalized ways of sectioning off the meat), then we discussed options for further breaking down the meat into secondary cuts that you’d find in a butcher’s front case (or shrink-wrapped at Wal-Mart).

We started with the suckling pig. I’ll get the gross questions out of the way right now: the meats were already slaughtered and cleaned by the time we got them, so there was no de-gutting or anything gross like that. I don’t think I could have handled it, really. I asked Tia how fresh this pig was, and she guessed less than a week old. “They’re slaughtered and cleaned, then aged for a few days to let them tenderize and stabilize, then we get them. We try to turn everything around within a week…that’s about the full shelf life for meat. We don’t freeze anything.”

After taking off the head (“There’s a lot of really great meat in there,” Tia tells us), we remove the trotters (feet…useful for stocks), hocks (the ‘forearm’ of the front legs) and the shoulders. One of the more interesting insights Tia highlighted was the artistry involved; ultimately a butcher’s goal is to entice you to buy his product, so offering tidily-packaged, neatly-trimmed and sliced meats is paramount. Anatomy, however, is rarely tidily-packed, so a lot of problem solving goes into navigating muscles and bones to yield an appetizing piece of meat. Tidying up edges leaves offcuts, which are ground and seasoned before being made into sausages or cured meats.

Tia mentioned that ‘old-school’ (no use of power machines) butchery is a dying art, and that most knowledge is passed just as we were doing: by word-of-mouth and asking someone with experience for a bit of help. Very little training is offered on large animal butchery because the meat is so expensive. You don’t want to turn a rookie loose on a $3000 cow carcass. Tia mentioned breaking steer down is mostly a service for her customers and not something she sees profit from, because they take up so much space and take so much time to butcher.

As we worked through the pig, Tia pointed out each muscle group and what cut it usually yielded. “This,” she tapped a paper-thin, nearly unnoticeable sliver of muscle inside the pig’s ribcage, “this here is the diaphragm of the pig. In a cow, this muscle is huge and an inch or two thick, so it’s easy and sensible to cut it out, and it becomes Skirt Steak. Here we can see the pig has the exact same muscle, but there’s no yield here and it’d be tough to get that out of there, so that’s why you never seek pork skirt steak.”

After finishing the pig, she took us back into the butchery’s meat locker, which had two gigantic sides of steer hanging and aging. Each side was easily a foot longer than I am tall; Tia pointed out all the muscles she’d pointed out on the pig, giving us an idea of scale and yield. “Fat content plays a decent role too. All this white stuff here is fat. When you age steak, you’re basically letting moisture escape slowly. This concentrates the flavor, and this big case of fat keeps the meat inside protected. In a goat, however, the meat is already pretty flavorful, and there’s very little fat to keep it protected, so we don’t age those nearly as much…there’s no gain there.”

We moved from the pig to a goat, which was very similar in structure and size. “To get through bones, you don’t ever wanna saw around on it with your knife. You’ll never get through it that way. We use a cleaver or a saw for that. You don’t rear back and bang around with a cleaver like you see in movies. We put the cleaver where we want to make a cut, then tap the spine of it with a mallet to help it through. It’s very clean and precise.”

There were two moments during which I almost passed out. I was a little surprised by myself; I’m absolutely terrible when dealing with stuff like needles (I almost fainted when Sarah got her lip pierced), but dealing with meat has never freaked me out. At one point I was a little lost in thought and was staring at Tia’s blood-covered hand, thinking “that would make a great photo”. At that moment she grabbed a piece of meat and pointed out some glands and ‘oogy bits’ that she recommended cleaning off the meat. One student asked what they were and why we wanted to clean them off. “Well, they’re not good to eat really, and aren’t visually appetizing. They’re just…”–at this point she started rolling the small, sphere-like sacs between her fingers–“…just gross really. So we’d throw these away, they’re not useful for anything”. My skin felt suddenly tingly and hot, and I recognized I was getting fuzzy-headed. The white noise crept up in my ears. Then I realized there were no seats, and nothing for me to really prop myself on, so succumbing to this really wasn’t an option (plus it’d make me look like a complete pussy to this girl who was nearly half my height, effortlessly holding a cleaver). I just told myself “Welp, self, this is happening, and you’re just gonna have to muscle through it”. I did, and within a few minutes I felt fine. Getting past it gave me a bit of a rush too…I felt a little like a badass.

By the end I was totally in love with the experience. It was way, way too much information way, way too fast for me to have absorbed all of it. If a suckling pig arrived on my desk I couldn’t at all effortlessly take it apart, but I could certainly make sense of it. And more than that, I DO know a lot more about the anatomy of the meats and would feel much more confident ordering at a butchery case now. I’m excited to take the next class (in August, in which we break down a full-size hog)…it will have familiar parts and will reinforce what I learned this time around.

Great post, Allen. I’m more or less a vegetarian, but I’m still fascinated with meat (too much of Bourdain’s No Reservations, probably), so it’s great to get a little peek of a butchering class. I probably won’t be attending one anytime soon. My vegetarianism is confused enough, as is.

I especially like shot with the pig head and other bits on the shelf and the cleavers in the background. Beautiful stuff!

Hello, love your project! I have a question for you. I have a lot of hydrocolloids and ingredients. some say they expire in the next two months like Lecithin and I just bought them, do they really expire, I mean, I can’t use them anymore?

Hi Norma;

I’m not sure really! But I can say that I’ve had some of my ingredients since I started this project two years ago, and I haven’t noticed any adverse effects from continuing to use them. I have some soy lecithin that I keep refrigerated and it still seems to work fine, and most of my white powders I keep sealed in jars. I would imagine (but don’t really know for sure) that the worst that would happen is the ingredients would lose their gelling power or might develop off flavors, but I haven’t noticed either of those things so I haven’t really felt compelled to throw them all out and buy them anew. I’m not sure this method of mine is very scientific though. 🙂

Thank you so much Allen! Very helpful! I live all the way in Nicaragua, Central America and I am wanting to start a similar project with the Modernist Cuisine. I travel to the states almost every month for different reasons, mostly business. I still need to find some ingredients and most important…equipment. I currently have sous supreme, among other very basic equipment like smoking gun, dehydrator, etc etc. What equipment do you think are most important in completing a project like this one?

Hey Norma,

This is such a good question I figured it’d be good to not bury the answer in comments:

http://www.allenhemberger.com/alinea/2011/06/equipment/