Not wanting to let forward progress in the cookbook fall aside, I worked on this dish at the same time I was making bubblegum soup, melting skittles, and baking hay. It was relatively straightforward to cook, but the presentation is especially awesomesauce.

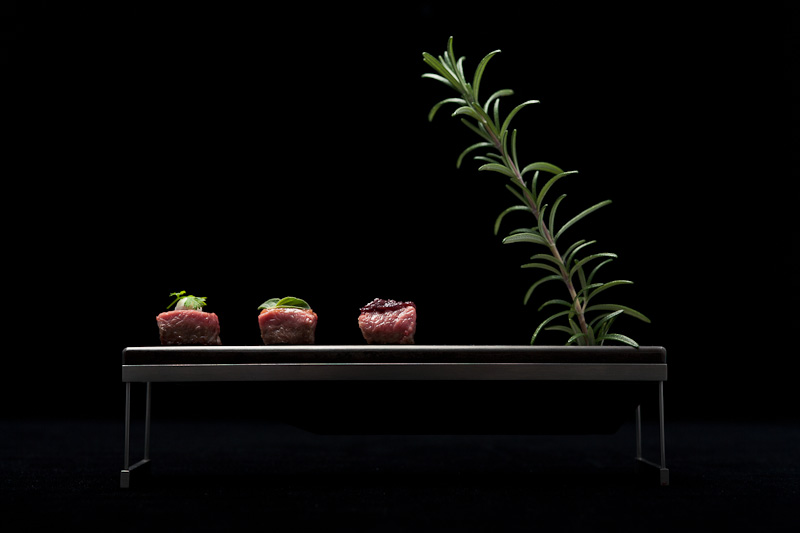

At Alinea, several courses before this dish is presented, a waitstaff member places an oddly-designed ‘bud vase’ on the table near each guest; the bud vase houses a bright, fresh sprig of rosemary that leans bouncily sideways. As the menu nears this course, silverware is removed and replaced with chopsticks, and we see the bud vase double as a chopstick rest.

The diner is then presented with a ‘brick’ suspended in a fine wire frame. Atop the brick are three small sizzling bits of meat topped with various garnishes, and a diner can feel heat emanating from the brick. The rosemary sprig is removed from the bud vase and inserted into a small hole at one end of the brick. Almost immediately, the air is thick with the scent of rosemary, the volatile oils being released by the heat of the brick.

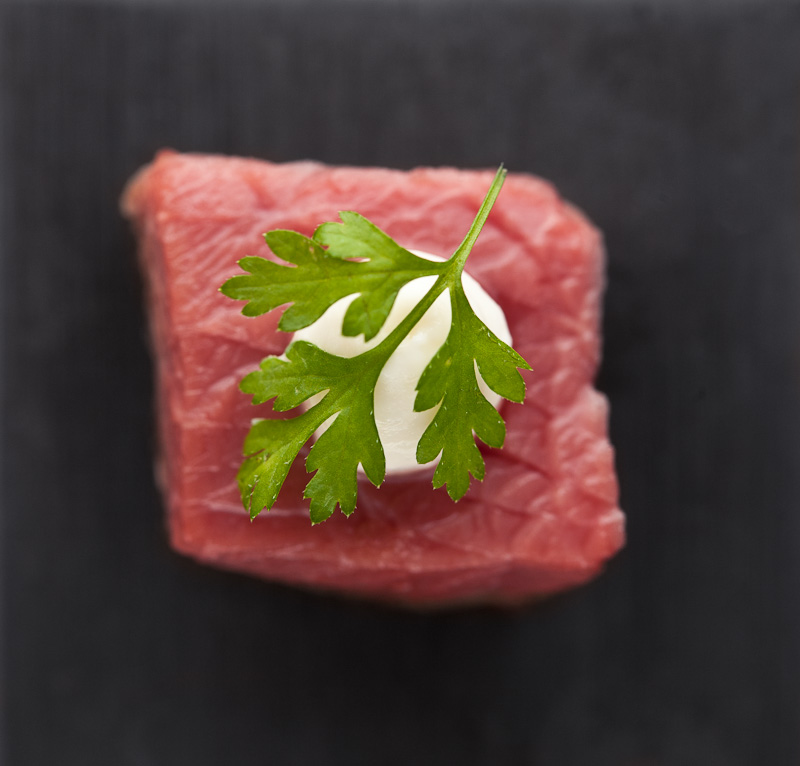

The three small bites of meat sizzling away are lamb. One is topped with mastic cream and a fresh small chervil tip. A second is topped with date compote and some young oregano leaves. The third bit is topped with a finely-minced cap of red wine-braised cabbage.

I don’t have a ton of “in progress” photos for this dish, largely because I was doing too many things at once. Probably the most interesting bit for me was securing some lamb; the last time I worked with lamb I was frustrated with my experience ordering it at a butcher counter because I didn’t really know what I was asking for. While I still have a lot to learn, my experience taking a butchery class has given me more confidence in knowing what to ask for and how to identify what’s being sold to me. At Berkeley Bowl, I asked the butcher if they had lamb loin. She gestured at some sliced lamb chops they had on display, and I shook my head and asked if they had a whole loin. She called over a manager, who nodded at me and went to the back. He returned a few moments later with a massive slab of meat. I asked if it was frozen and he shook his head no. I asked him to unwrap it so I could see it and weigh it; he asked if I wanted just the loin (the cut still had the two side flaps attached, which I knew wouldn’t serve me at all and would just add extra weight/cost to the purchase), and I said yes. So he trimmed it down, weighed it, and looked at me when the scale read out $83 for the slab. (At this point Sarah, exasperated by my insistence on buying this and prone to anxiety when she goes shopping with me because of this exact experience, shook her head and sighed “I’ll be over by the beer” as she walked away in frustration). I looked at the butcher and mulled it over, but before too long had passed he punched some more buttons and the price dropped by $10. “Ok, I’ll take that” I said.

I get why Sarah dislikes this, and it’s amusing to me that I, inversely, really enjoy it. There’s a rush for me that’s fueled by the excitement of knowing that I know something I didn’t know before. Being able to buy exactly what cut I want (and to know what I’m doing with it when I get home) is, to me, a mark of what I’ve learned. That’s quite satisfying.

At my butchery class, we cut the loin (which contains several long muscles running alongside the spine…if someone gives you a backrub up and down your back, the long vertical muscles they’re rubbing are these same muscles) into english chops, which involved cross-cutting the loin into tidy individual portions. For this dish, I wanted the loin intact, so I cut it away from the spine in one long cut. This yielded two sirloin strips and two tenderloin strips; I vacuum-sealed and froze the tenders and one of the sirloins, leaving me one remaining sirloin to cook sous vide at 57C for about a half-hour, packed in olive oil.

For service, the loin was cut into 3/4″ cubes, then seared on one side in a bit of oil in a hot pan. The cubes were garnished before being placed on the brick (Alinea originally used terra cotta bricks, but Martin at Crucial Detail did a run of cast-iron ones, an extra of which he sold me a while back and which I’ve been looking forward to using on this dish ever since). The brick itself is heated to 500F in an oven before service.

The pairings of the garnishes with the lamb were tasty for the most part; Sarah and I agreed we found the mastic pairing to be the least-amazing of the bunch. Mastic has a pretty distinctive taste, and it with the lamb didn’t seem to yield something more than the sum of its parts. The date and oregano combination was our favorite; the sweetness and pepperiness of the date compote and the warm depth of the oregano was delicious. The texture of the lamb bits themselves was also nice, going from a crisped ‘bottom’ to the medium-rare ‘top’, and the deep, fresh scent of rosemary vapor hanging in the air made both of us want to sniff deeply as we ate each bite.

The one thing I seem to consistently be underwhelmed by is the flavor of the meat itself. I think I must be doing something wrong, because on almost every Alinea dish so far, sous vide meat has been surprisingly less interesting than I’d imagine. There’s not a ton of flavor other than mild ‘meat flavor’, which itself never strikes me as delicious as, say, a great grilled steak that’s been seasoned and left to marinate for a while. Maybe I’m doing something wrong in how I finish it? The sous vide step I’ve got down pretty well (cook to medium-rare), then I chill the meat, cut it, and store it in the fridge under a damp napkin until I’m ready to finish and plate it. I take it out of the fridge and sear it usually, but the meat usually never gets super-warmed-through before the searing is complete, so the final product is sort of “lukewarm” in temperature, and blase in flavor. What could I do to improve this?

Hey – I’m a friend of Mike Frederickson and found your blog through the link he posted on facebook. This is a very cool site. A few observations about your meat-underwhelmingness problem.

Is your meat dry aged at all? In my experience, a lot of restaurant meat is aged in some way which adds a very different dimension to it separate from any seasoning. The other tack to take would be to brine or dry brine the meat for a day or two before you cook it – it adds more than just the salty flavor to the meat since it also removes moisture which won’t be lost in sous vide cooking like it would be in normal roasting and so allows you to concentrate the flavor in a way that sous vide won’t accomplish.

In terms of temperature, why not just stick the meat back in the sous vide until it comes back up to temperature and then quickly brown it. There’s no real risk of overcooking it in that context and it will bring the meat up to the ideal temperature. The only issue with that is that the meat can more easily overcook when you sear it but that merely requires more attention.

I love your process though, it’s totally fascinating. Can’t wait to see the end of it.

Hi Deanne! How rad; nice to meet you! May I say your taste in friends is impeccable.

Thanks so much for the tips! They totally make sense to me; I tend to be in a constant state of vacillation between applying intuition like what you describe and following the cookbook’s recipes as accurately as I can. They don’t mention anything about pre-aging or brining meat as a general rule, but I might well try that for the next dish involving meat I try. Certainly it couldn’t hurt.

I think your re-warming idea is a good one as well; again it’s not something the book mentions, but I’d like to try it to see what improvements in flavor it’d offer.

Anyway, thanks for all the advice, and for feeling compelled to write in general!

I’m no expert but I was going to say a similar thing as Deanne. I would think the meat would have to be at least room temperature again before you sear it.

As for ageing meat…I could never figure out why my steaks weren’t as nice as the ones from a restaurant until someone told me to specifically ask for aged beef. I’m not sure about where you are but here it’s all too easy to buy cuts that are too “fresh” 😉 So now I ask and I think 2 weeks is a good start – no idea about lamb though! I assume it would be similar.

I am a bit surprised to hear your comments about the meat cooked sous vide. A good cut of meat should taste good if cooked properly and you cannot get more precise than sous vide. The quality of the meat is especially important here (even more if it is not heavily marinated or seasoned) but there are a few steps you can take. One of them is the aforementioned process of re-therming the meat to the desired temperature, salt it and then sear it well for 30 seconds to a minute per side. That’s what I usually do. Adding a tablespoon or two of butter and maybe some herbs to the bag is also a good idea. Another way is to grill, sear, or even smoke the meat briefly and then bag and cook it SV. This latter method works especially well for long SV cooks (24-72 hours) for stuff like short ribs, spare ribs, chuck beef,…

It should definitely be warmed all the way through before you eat it.

90% of the time I’m cooking meat sous vide now, I also give it a pre-sear. Process is to dry the meat very well, then sear in an extremely hot pan, chill, bag, cook sous vide, remove from bag, season, sear again, rest if applicable, serve.

The pre-sear means some of those browned flavors will permeate the meat as it cooks, but it also means that the post-sear achieves a much richer and more complete browning. Huge improvement.

The process is a game changer for items with a fat cap that ideally gets rendered. Poultry breasts, for instance, tend to do very well when cooked sous vide, but their skin is usually limp. By giving them a pre-sear (not necessarily on high heat–with duck breast, for instance, it’s best on a medium heat to allow longer rendering) then cooking sous vide, you can post-sear quickly and without overcooking but still achieve deeply browned and crispy skin.