I came home and did some research about umami. It turns out we were both wrong; the human tongue has receptors for L-Glutamate (an amino acid), positioning it as a fundamental flavor for us. Since we can taste glutamic acid, it follows that foods that are rich in this stuff can be said to have glutamic acid–or umami–flavor. There are lots of foods that contain glutamic acid: ripe tomatoes, cured meats, shellfish, and most fermented things (including soy and Worcestershire sauce). Maillard reactions in browned protein release glutamic acid, contributing to the taste of umami. Seaweed is extremely rich in glutamic acid, which is why Japanese dashi (broth, typically made with kombu and dried bonito flakes) typically represents the most idealistically-pure example of the flavor.

In 1907, a professor at Tokyo Imperial University isolated crystals of glutamic acid left behind after evaporating a large quantity of seaweed broth; these crystals exactly encapsulated the ineffable but undeniable flavor of umami. The professor went on to patent a method of mass-producing these glutamic acid salt crystals, known as Monosodium Glutamate (MSG). MSG, then, is pure distilled umami.

MSG is interesting in that it typically doesn’t taste pleasant in and of itself; it usually requires an aroma component to be found tasty. It also rapidly becomes unpleasant in concentrations of more than 1%. It’s been found to be a useful flavor booster in low-salt foods.

This dish is listed in the Summer section of the cookbook, but I chose to do it now because I’ve learned that springtime in the Bay Area carries with it a bounty of ramps–one of the hero ingredients here. Ramps are part of the Allium family (think onions, garlic, leeks, etc.); they have a garlicy smell and an onion-like flavor. I learned they’re pretty popular in Southern food, but even though I’m from Kentucky originally I’d never tasted them before now.

I called both Jerry and Marin Sun Farms the Tuesday before making this dish to inquire about ordering pork cheeks. Ver Brugge told me they needed to special-order them by the pound, and asked me how many I needed. I told them between 4 and 8; if I can get at least 3 platings I’m good. Marin Sun Farms said they often get pig heads in for the weekend and would be happy to take out the cheeks for me, though the girl I spoke with added with a hint of disaffected cynicism “we don’t have the best track record for getting customer orders taken over the phone in, but come in Friday to check anyway.” I hedged my bets and placed orders at both shops, then went to visit both on Friday afternoon after work.

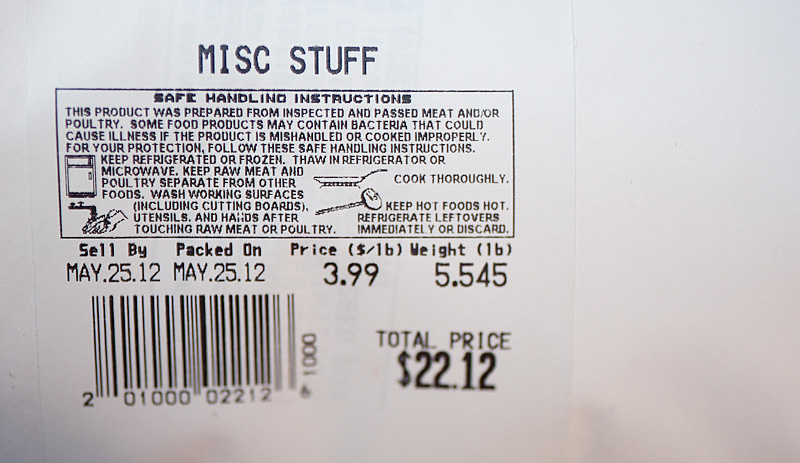

Jerry at Ver Brugge offered me a large plastic bag filed with inscrutable and obviously-unbutchered ‘stuff’, saying “Here are the jowls you asked for” (a comment I thought innocuous at the time, so romanced was I at Jerry’s bad-assedness). They charged me $3.99/lb, a total of about $22 for the lot, and Jerry said “Yeah there’s maybe 4-5 pieces in there”.

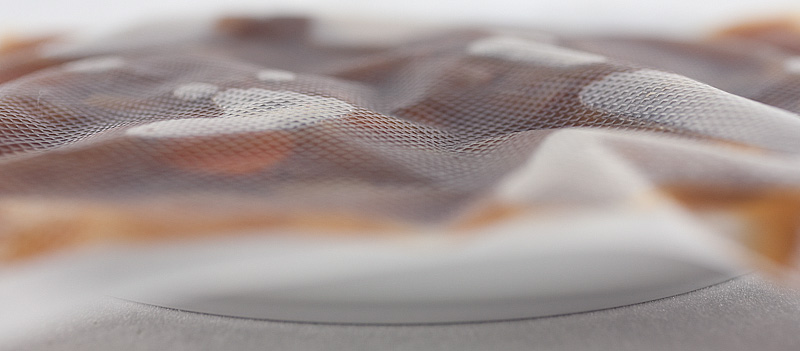

I approached the counter and mentioned I’d placed an order on Tuesday for some pork cheeks; the bespectacled 20-something behind the counter hunted around a bit before producing a small, tidily-sealed pouch of bright pink meat. Because the bag was sealed, I couldn’t really see what was in it, but I did notice the price: $9/lb. “This is kind of a rough price” I winced to the guy, who regarded me a hair above apathy.

“Yeah? Where have you seen a better price?”

“Ver Brugge, right up the road. They’ve got cheeks for $4/lb.”

“Never heard of them. Are they organic?”

Ugh. Damn you, hipster, of course you’ve heard of Ver Brugge. But I’m 99% sure this bag I had in my hand from them wasn’t organic, so I shook my head in the negative.

“Well. Yeah. We’re all organic and pasture-raised.”

“That costs over twice as much?” I asked.

“Well. Yeah.” he shrugged.

“Just gimme the bag.” I felt like I was being ripped off, but I also was DOING SCIENCE, and we all know you can’t put a price on science.

When I got home, I unwrapped the two parcels of meat. The Marin Sun Farms parcel immediately threw me into regretful territory; for nearly the same price I’d paid for whatever was in the Ver Brugge bag, they’d sold me 8 extremely-beautifully-butchered pork cheeks.

I mean, look at these!

Point: hipster butchers.

The pork cheeks were marinated overnight in a mixture of Worcestershire and white wine that was cooked with carrot, leek, and onion. This marinade was vacuum-sealed and cooked en sous vide for several hours; the book specified 5 hours for the cheeks, but the portions from Marin Sun Farms were fairly large, so I ended up letting them go for close to 8 hours (I poked at the bag every half hour or so to test for tenderness).

At the same time, I blanched some heart of leek, figuring the gentle onion-garlic “allium-y” taste of them might be substituted reasonably this way. I held the leek hearts with the green garlic batons.

The pork cheeks are topped (hidden, even) by a mound of gruyere cheese and crispy pumpernickel chips. The former is made by grating gruyere into long, thin strands with a microplane onto some parchment and left to dry for a day. I ended up with hard, crisp little curls of gruyere (which apparently is exactly what I was after. They were admittedly kinda neat).

For the pumpernickel chips, I was meant to shave frozen pumpernickel bread on a meat slicer into very thin slivers to bake in the oven, but my borrowed meat slicer from a few weeks ago had been returned so I was left to do this with a knife. It sucks; you just can’t do it right. The best I could do was chip off reasonably-thin (but uneven) slivers that I baked in an over until all their moisture was gone (you bake it at just over 212F, so the water evaporates but little ‘cooking’ is done). I mixed these chips with the gruyere and stored them in a container until service; they tasted great but didn’t quite have the impossibly-delicate crispiness they’re meant to.

To plate, I first put down a small spoonful of the onion-raisin sauce, followed by a spoonful of the onion-raisin-garlic ragout. This was topped with the warm, crispy pork cheek portion and one of the leek hearts, then covered completely with the dried, crispy gruyere-pumpernickel mixture. I played a bit with the leek hearts vs the small green garlic batons; they both tasted nice, but the leek heart was more fun to eat and I also thought it looked more striking, so I went with that version to photograph.

I’m also really happy (and surprised) at how much I liked photographing it! I pictured in my head a lot of beige and brown and thought it might look rather boring, but I found the bright burgundy of the ramps and the splashes of green from the chives, broccoli, and leek very springlike and arresting. I might like these photos as much as I like the avocado/lime ones (which to date I think might be my overall favorites).

Mmmm, pickled ramps

Also, I’m going to up vote Marin Sun Farms (I heard some college kids use up vote in a sentence this weekend, so it’s obviously the cool thing to do). I get their CSA box and they are a really nice meat place to work with. I agree that the Rockridge butcher shop is more hipster than butcher but their Sunday spot at the SF Ferry Market and their flagship store in Point Reyes are pretty awesome in terms of selection and helpfulness from the butcher – although it’s not so much a butcher at the Ferry Building market. Also, their meat tastes amazing. It kind of ruins supermarket/Costco meat for me.

Bonus point: If you like camping or distance cycling, it is really fun to go up to Point Reyes and either camp at the national seashore or go for a long bike ride in the area and then end your adventures with a burger at the Marin Sum Farms store in Point Reyes. One of the best burgers ever.

I can’t tell from that photo whether those “jowls” also include pork cheeks, but I can tell you that when I got beef cheeks wholesale (untrimmed) recently, they just looked like a big mess of flesh like that, and the yield after trimming was only about 1/3 of the original weight. So it’s possible. But they took an insane amount of time to trim well. Those Marin Sun Farms cheeks are gorgeous.

Also, we leave out some meticulously-prepared component every single dinner. Often some garnish like a chip. In the rush of plating we just forget to include something.

Harold McGee has a nice little piece about umami in the first issue of Lucky Peach, but based on what you’ve said in this post, you’ve probably come across everything the article has to say anyway.

The dish looks awesome. I’m a fan of your use of flowers to garnish things recently. Too bad about your green garlic chip–very cool looking…science-fiction-y.