Oxalis might be the most annoyingly-vile weed ever. It looks a bit like clover, but it has these funky, torpedo-shaped ‘fruits’ it produces after flowering that, when touched in even the slightest way, launch seeds explosively and generously. The seeds are quick to sprout and seem indestructible, producing another plant within a few weeks. I’ve been waging battle against this stuff in our yard since we moved here; no amount of pruning and pulling seems to eradicate it, and every time I accidentally brush one of Oxalis’ seed pods and those little seeds go flying, I think “DAMN it”.

This weekend I moved into a new tactical phase with the stuff; I ate it.

Oxalis is hands-down the most lowly, un-exotic ingredient in Alinea’s cookbook; not recognizing the plant, I scoured several exotic seed catalog sites trying desperately to find “Wood Sorrel” (Oxalis’ common name) seeds. I went to the Berkeley Horticultural Nursery and asked if they sold it — they looked at me like I was nuts, but I wasn’t sure why. It wasn’t until I asked at work if anyone knew anything about this plant that my friend Pauli replied “Yeah, my boyfriend’s been trying to get rid of that shit from our backyard for years. You can have as much of it as you want”. It was at this point I looked in my own backyard, and sure enough, this stuff was already occupying about half of it.

Oxalis is an extremely-common ground-cover plant that resembles clover and tastes sort of like Lemonhead candy; it’s tart/acidic and has an earthy, grassy note. This is due to presence of Oxalic Acid (huh!); Oxalis is one of the primary sources for harvesting Oxalic Acid, even. In high doses, Oxalic Acid is toxic and can be fatal, but chewing on leaves from an Oxalis plant gets us nowhere near these levels any more than a sip of vinegar poses a danger of death. Both the leaves and the seed-laden fruit of the Oxalis plant are edible.

In this dish, the Oxalis pods are a tangy garnish for Squab, Strawberries, and Thai Long Peppercorn custard. This dish as a whole is incredibly relaxing to make; it’s an exercise in patience rather than dexterity, so it made for a really nice weekend project. There are a lot of “Do this, then wait 5 hours, skimming form time to time”-type things going on here, so be ready for it to take a solid couple of days to complete, but be ready to drink a lot of beers in the down times too. It’s the high-end equivalent of making BBQ in a smoker. A nice benefit to this is that I had lots of time to take more photos than I usually can.

This recipe starts with 4 whole squabs; I found these for about $12 a pop at Berkeley Bowl. They’re smaller than a Cornish hen, and are usually sold in the freezer section (since they don’t tend to move nearly as fast as chicken or other more-common meats).

After thawing the squabs gently overnight, I broke them down; I trimmed the breasts into a diamond shape, and separated the tenderloins. I removed the legs and gizzards, and separated these from the carcass. Everything gets used in this dish.

I vacuum-sealed the breasts and tenderloins and put them in the fridge to store overnight; on the first day I wouldn’t be needing them so I wanted to keep them in good shape.

I rinsed the legs and gizzards, and while they were left to drain in the sink, I toasted some thai long peppercorns. I *love* the smell of these things, and Sarah inverse-proportionately hates them. A minute after I started toasting them she called down from our loft “What are you doing down there? It smells like a church in here.” If you’ve ever visited a Catholic mass when they fire up the incense, you might have an idea of what this smells like. I really find it intoxicatingly complex and interesting.

I ground the toasted peppercorns in a spice grinder, then mixed with equal parts sugar and salt, yielding a Thai Long Peppercorn Cure. I packed the legs and gizzards in this cure and left them in the fridge for a few hours.

While the legs were curing, i cut the rinsed squab carcasses into small pieces with some kitchen shears. These would go into making Squab Stock.

The pieces are browned in a roasting pan, then cooked a bit longer with fennel and onion. After this has sweated for a few minutes (the book is very specific not to allow anything to brown to the point of caramelization), I transfer the mixture to a large stock pot, trying to keep out as much rendered fat as I can.

I add some thyme, peppercorns, vermouth, and tomato paste, then let this mixture simmer for 5 hours. The smell of this is amazing to me; the vermouth-fennel combination is something I imagine must have a specific name (and I bet it’s French), it seems so fundamentally-perfect. During the simmer, I skim the stock every 15 minutes or so, to remove impurities that have collected near the top. I move the pot partway off the burner so that the convection currents push the impurities to one side, so it’s easier to skim.

While this is cooking, I toast some more Long Peppercorns, and again grind them to a fine powder.

This powder is mixed with some cream, sugar, and salt, and brought to a boil over medium heat. I then let it steep for 20 minutes or so, to allow the cream to absorb as much flavor from the peppercorns as possible.

After the steeping is complete, I add some Iota Carrageenan, a stabilizer that can form soft, elastic gels in the presence of calcium. The carrageenan is hydrated by both high temperatures and high shear, so I hit it with an immersion blender as I bring it to a boil again, blending for about a minute before straining the mixture into a shallow pan to let it cool. The pan is lined with cling wrap (I sprayed the pan with a bit of water first, to help the cling wrap stick to the bottom better, which lets me get it smoother. Wrinkles in the cling wrap make it hard to get the resulting gel out later), then left to cool until the gel sets. The amount used here yields something of the consistency of Key Lime Pie: a smooth, custardy texture that tastes either really lovely or like a church, depending on your polarization.

By this time, the legs and gizzards had cured, so I removed them from the fridge and rinsed the excess cure from them.

I packed the legs and gizzards separately into vacuum bags, and sealed them with some canola oil. These were cooked in a warm water bath for another 5 hours or so, then chilled overnight in the fridge.

While the legs/gizzards were cooking, I finished the stock; I strained it and reduced it, continuing to skim until it was reduced by half. The “reduce something by X” thing was always a point of confusion for me until Erik showed me this pretty cool trick: grab a wooden skewer at the beginning of the simmer and dip it, marking the depth of the water line. Then, cut a notch at the halfway point (or whatever point you need to reduce to); then you can just keep testing until you hit the notch.

The next day, I started by working on Strawberry Sauce. I first pureed some fresh strawberries with some red wine, red wine vinegar, and sugar.

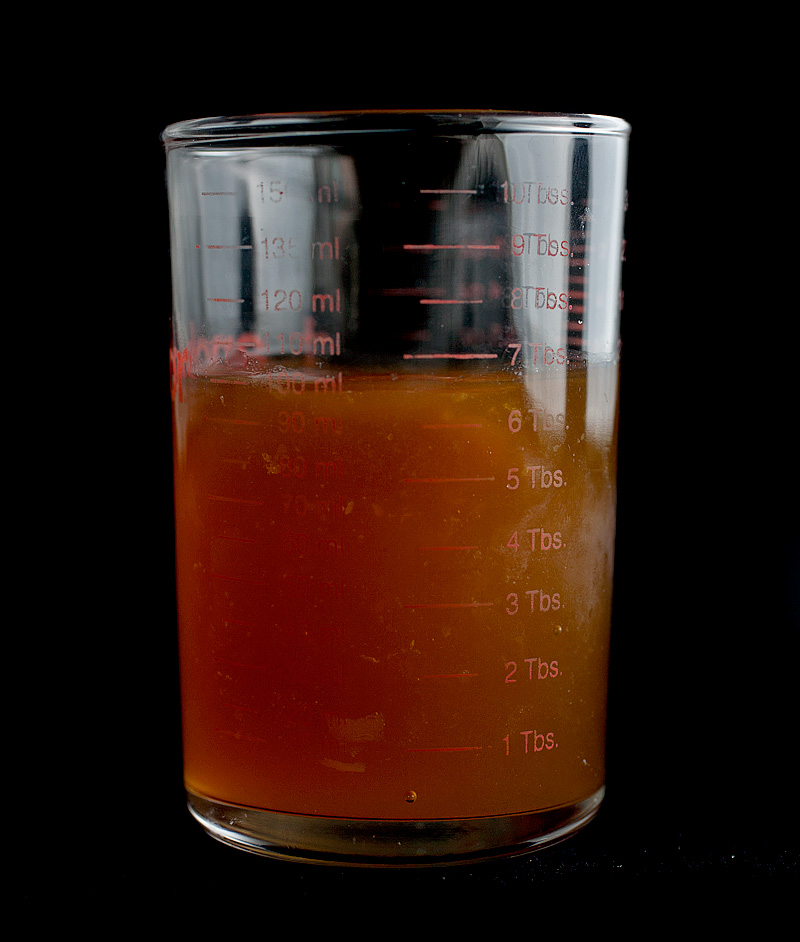

This mixture was simmered with some of the squab stock until it was reduced to something the consistency of BBQ sauce.

Next up was making Neutral Caramel Squares, which ultimately sit atop some skewered Oxalis pods. To start, I mixed some fondant, glucose, and isomalt in a saucepan.

A couple of years ago, I did some experiments to wrap my head around the nuances of various types of sugars like those used here. While that experiment didn’t really pan out the way I wanted, I learned a ton and got to leverage some of that here. Isomalt is a sugar that does not caramelize the way cane sugar does (at 325F, cane sugar browns [“caramelizes”] from the Maillard reactions occurring at that temperature. Isomalt does not undergo these reactions). Inclusion here helps offer a ‘buffer’ to the fondant and glucose (which CAN brown), because we ultimately do not want browned sugar for this recipe. The cookbook further instructs me to cook this mixture to 160F, “taking care not to allow any browning”. This is a misprint; at 160F we haven’t even gotten rid of most of the water in the mixture, much less do we run a danger of burning anything. I saw this and almost-immediately recognized it to be wrong, largely because of all the mistakes I’ve made doing this in the past.

The “hard crack” stage of cooking sugar (which is the point at which, if you cool your mixture, it forms a hard, crackable candy rather than something like taffy or syrup) is around 310F. “Caramel” stage is 320F-325F; for this recipe, we want a hard crack sugar, and we want to get it as close as possible to the caramel stage without blowing it and causing any browning. A different recipe in the book targets 316F for this purpose, so that’s what I aimed for here. After it hits this stage, I pour it out onto a prepared sheet tray and let it cool. We can see here I incurred a bit of browning but not too bad; some of the browning carries with it some nice complex flavors and keeps this from tasting like straight-up neutral sugar.

I broke this “sugar glass” into shards and ground them in my spice grinder to yield a white, snowy, fluffy powder.

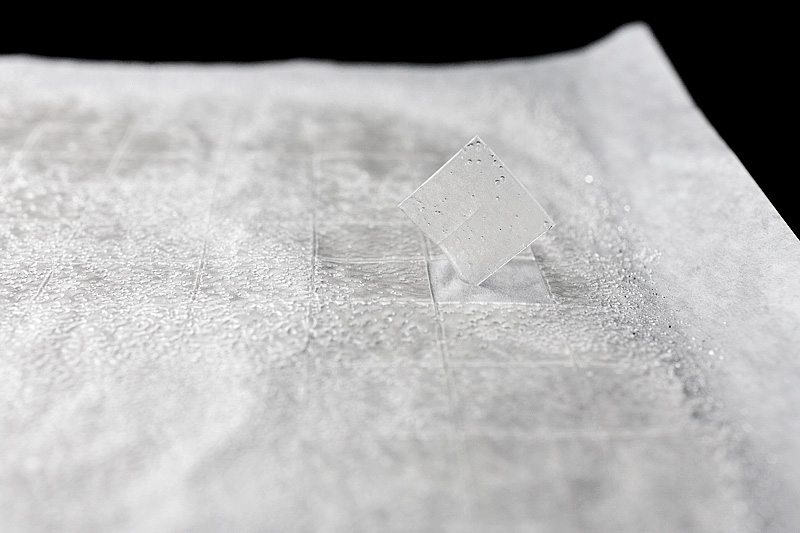

This powder is sifted through a strainer onto another sheet tray lined with teflon-coated paper.

It’s then baked at 425F for just a few seconds, to allow the powder to melt. The longer you melt the powder, the more surface tension starts to take over and cause things to bead up into bubbles, so this really only needs to take a few seconds (the book mentions 6 minutes, which is way too long for my oven). Once I had melted it, I removed it and quickly cut it into small squares, then left the sheet to cool on a rack. After a few minutes, you can peel up the squares; they’re very thin and delicate, and super-crisp.

While the sugar was cooling, I diced up some more fresh strawberries into small dice…

…and cut up a few others into bigger bits. These bigger pieces were macerated for a while in a mixture of red wine and sugar.

I rewarmed the cooked legs and gizzards in another warm water bath, then removed the meat from the legs and minced up the gizzards. These are combined with shallot, butter, more squab stock, salt, and a dash of red wine vinegar to make Squab Rillettes.

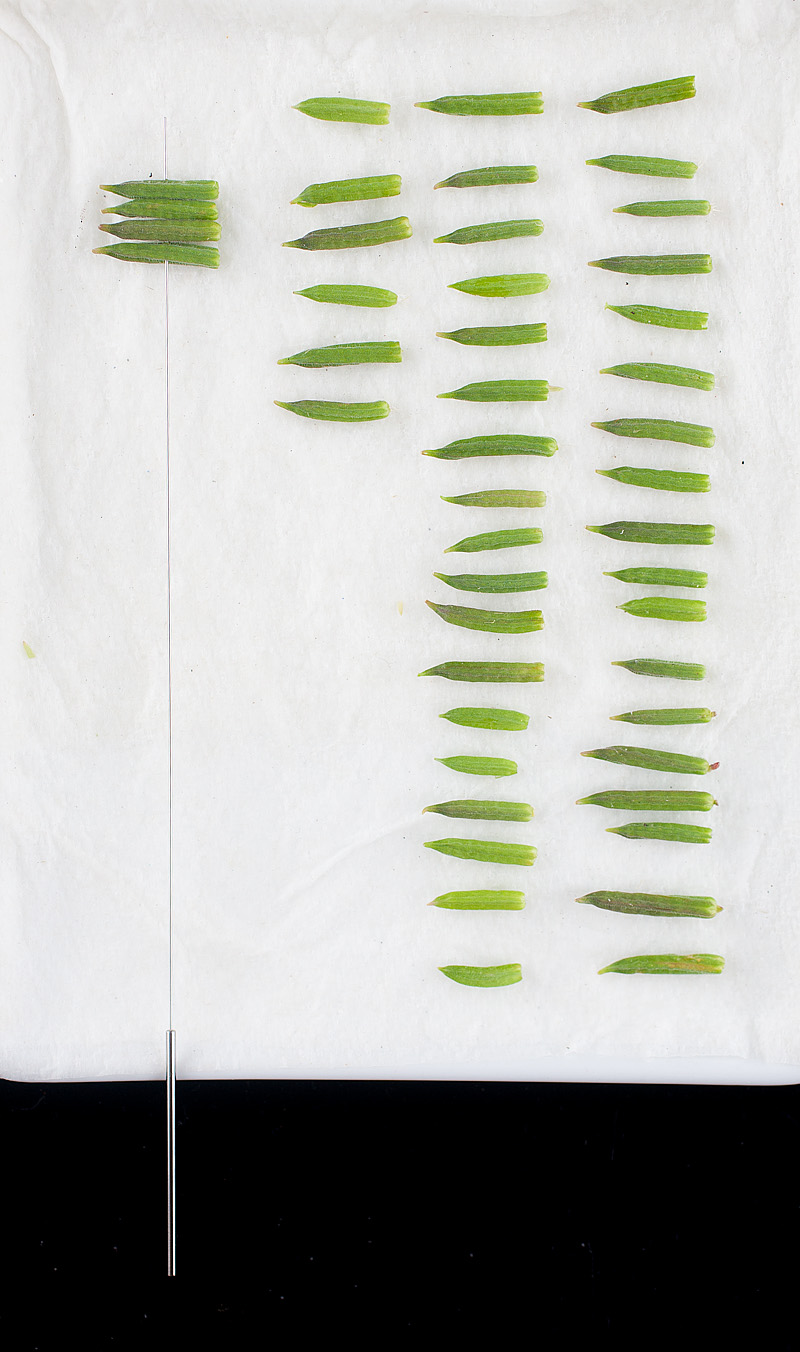

The last step before starting the plating process was collecting my garnishes. I went out to our yard to do some glorious weeding, carefully collecting several dozen Oxalis pods.

I also gathered some of the nicer-looking Oxalis leaves and flowers, as well as some sorrel from the garden.

And finally, I decided to use some micro Ice Lettuce that I’ve been growing. I first came across this pretty-fascinating plant last year at the French Laundry. It’s a crunchy, mildly-lemony succulent that’s covered in crystalline, dewdrop-looking capsules that look like frost crystals (so in these photos, the ice lettuce isn’t wet). It’s just so damn pretty and interesting that I had to try growing some.

To begin plating, I heated some canola oil and seared the reserved squab breasts, crisping the skin and browning it nicely while basting with melted butter. At the same time, I seared the tiny squab tenderloins, and let both of these rest while I assembled the rest of the plate. I spooned a puddle of the strawberry sauce in the center of the place, then added mounds of strawberry dice, rillettes, and a cube of the long pepper custard.

I sliced the breast into several bite-sized portions, and placed these in the sauce. Then I garnished everything with my collected greens.

The final step was placing a caramel square on top of the skewered Oxalis pods, and warming it gently with a kitchen torch to melt it into the pods. This was placed on top of a macerated strawberry, and the whole thing sits on the rillettes.

For as much as I loved this dish, Sarah exactly disliked it. I find squab to be an intoxicating flavor; when I worked with it last year, it was paired with foie gras and licorice, and I found the flavors to be over-the-top opulent and delicious. I chalked it up to the inclusion of the foie, but it turns out that squab itself is very rich and opulent. The idea of pairing it with tart flavors (licorice and watermelon last time, lemon and strawberry here) helps cut the richness and keep it balanced. The long pepper pairs excellently with it, adding a depth and complexity that I find quite compelling. But apparently squab is a bit polarizing; last time I worked with it, a couple friends didn’t finish their plates (including Sarah), and she reminded me this time that the flavors here just really aren’t her thing.

She conceded, however, that the raw strawberry dice were to her liking. So that’s a feather in my cap.

Can I seriously come hang out with you sometime?? Your attention to detail while cooking through this book is just exquisite and the photography is just out of this world. Fantastic job, you’re truly an inspiration!

Happy Blogging!

Happy Valley Chow

Aw dang, thank you eric!

Man, those macerating strawberries look so luscious.

Heh, thanks! I was pretty excited by how that one turned out. It’s way more cinematic than I’d planned it to be.

160F, should have read 160C (about 320F), do you think? Seems like an easy slip for them to have made…

Great job pulling together all the elements for that dish! Very impressive!

Hey Jonathan!

Huh, that does seem like a reasonable guess! I’m not great at doing the conversions in my head, I probably should have spotted that more obviously. Thanks!