The story of this dish starts the way the recipe for it in the cookbook does: with stock.

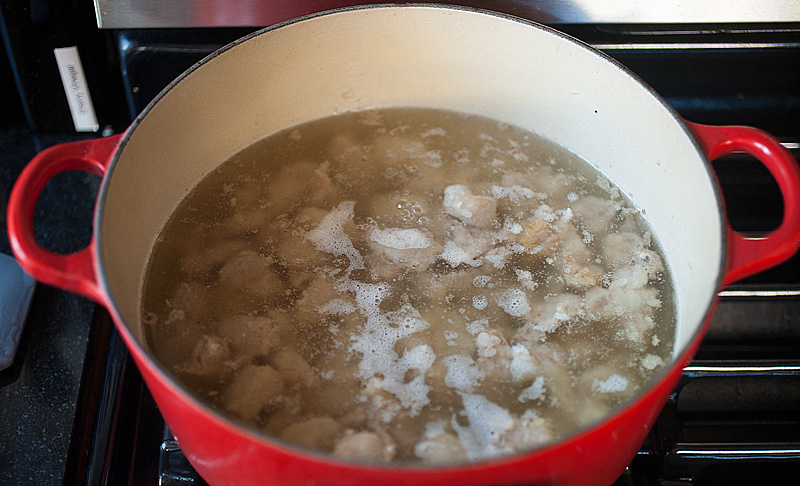

Among the most time-consuming tasks in this cookbook — instanced 4-5 times throughout it — is creation of veal stock. Chef Achatz’ roots at The French Laundry are belied in the recipe for it, although rather than TFL’s three-day process, Alinea’s is a bit more streamlined: it involves blanching 10lbs of veal bones, simmering them for 8 hours gently, straining them, simmering them for another 8 hours, then reducing the combined 1st and 2nd pass to a liter’s worth of rich stock. The first time I made it, I naively just saw the two 8-hour instructions and surmised I might be able to do the whole thing in one long day. Nope. Factor in the time it takes to bring several liters of water to boil (thrice) and how long it takes to reduce the final stock and you quickly run into a 2 day process, and if you’re going to take a break overnight, don’t forget to factor in how long it takes these massive pots of water to cool before trying to put them in your fridge.

In short, it’s an involved process.

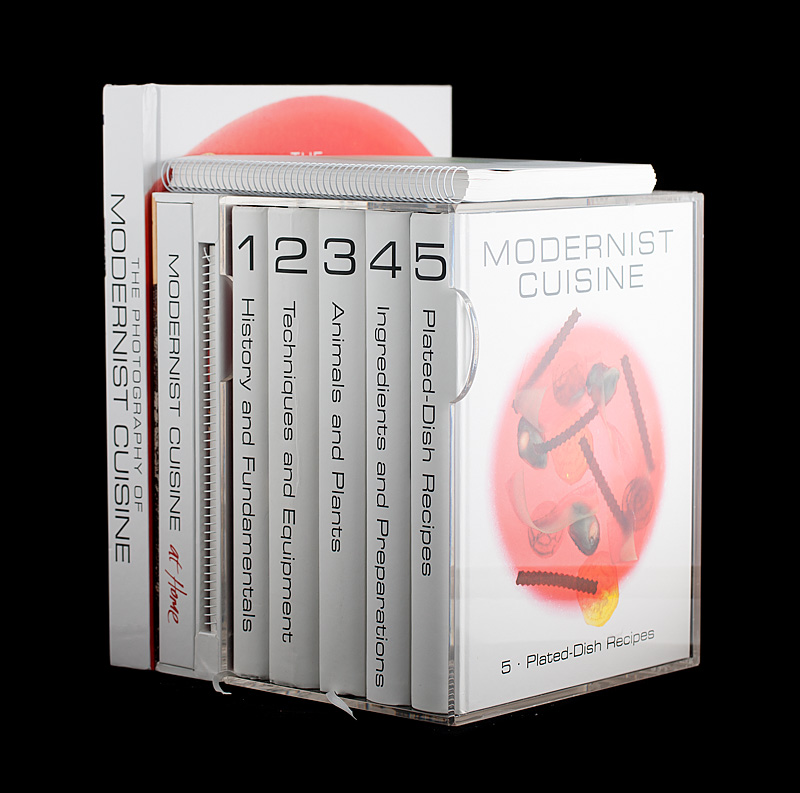

Several months ago, I mentioned being fortunate enough to be included in a roster of food blogs presented by Saveur. A cool side-effect of this was getting to meet a couple new people as a result, including Scott Heimendinger. Scott and I struck up a conversation that eventually drifted around to talk of me doing a small freelance project for Scott’s ultra-cool day job. When discussing payment for services, I asked Scott if Modernist Cuisine might be interested in a little trade. He agreed, and a short while later our apartment got notably heavier.

Most early critiques of these massive books seem to dance around saying anything super-committal one way or another about them…other than “they’re really big”. Many said something like “they read like textbooks”, which seems like the literary equivalent of looking someone up and down and saying “Huh. You changed your hair.”

I can’t quite understand that trepidation; I’m nearly through Book 3 of the main collection and it’s fucking awesome. Staggeringly-beautiful photography aside, the Modernist team strikes a really lovely balance of positing information without sounding arrogant or de facto about it; there’s a refreshing humility to bits of it that are surprising given such an ostentatious physical presentation. Many concepts are familiar but the team dives deep on everything, ensuring that they (and the reader) fully understand the whys and hows of cookery. As an artist who understands that making cool shit is expensive, I find the unarguably-hefty pricetag a justifiable one: a team of dozens of people spent years building the collection, it wasn’t easy and took a lot of time and consideration. A full-page photograph of an intact and wholly-skinned monkfish along with a frank caption attesting that it took a chef a full day to accomplish this is one of countless examples of the effort that went into the books. While the ordering of things is a little scattershot, the sheer amount of interesting information makes me really love these things (learning how KFC fries their chicken is one of my absolute favorite bits).

So as I read through this Alinea recipe several weeks ago in trying to plan for it, it was with particular acuity that the sections of MC Book 2 about pressure-cooking stock caught my attention.

The short version is this: traditional methods of cooking stock involve long, slow simmers of bones with aromatics — long because the collagen surrounding the bones and the marrow within them need low, steady heat to give up their flavors. Water can’t ever boil over 100C under normal conditions, and the jostling of bubbles in a rolling boil cause the stock to go cloudy, so the conventional way to deal with this is to simmer gently, yielding a clear stock. The longer time necessitated by the low temperature of around 90C mean that the stock undergoes an enormous amount of evaporative cycles as it cooks. Cooking stock makes your kitchen smell great; this is because aromatics cooking in the stock are escaping via the steam emitted from it as it simmers. Because you’re constantly purging the stock of aromatics, you need a lot of them per batch of stock. So, making stock this way is relatively expensive in both time and ingredients.

Modernist Cuisine describes a more efficient way to do all this: via a pressure cooker. Once pressurized, a pressure cooker cannot boil (the vapor pressure inside the chamber is so high that the water can’t evaporate) and becomes superheated well past 100C. This increase in temperature makes all the reactions that happen in traditional stockmaking run faster, and the lack of violent boiling yields a non-cloudy stock. Because there’s no evaporation, aromatics aren’t purged during the cook, which means you can use way less of everything to yield the same ‘strength’ stock at the end. The books describe a recipe for veal stock that cooks in about 4 hours.

This sounded like a pretty fun thing to try, but I was curious how the Modernist recipe would compare to Alinea’s when it came to final flavor. I decided to try a rough test: I would make 3 batches of stock. The first would be Modernist Cuisine’s pressure-cooked stock. I would also cook the exact same recipe in a slow-cooker, mimicking the more traditional approach but without the heavy evaporation problem normal stock has. Finally, I would try as best I could to port Alinea’s stock recipe over to the pressure-cooker ‘style’. This last bit was the hardest; I wasn’t sure how to reliably convert Alinea’s quantities down to those appropriate for this other method, so I just did some guesstimation.

Modernist Cuisine’s recipe involved a step Alinea’s does not: they roast their veal bones in an oven to brown them before putting them in the stock, and also brown all their aromatics before adding water. As the MC stocks were cooking, I read a little about this. Turns out the difference between “brown” stocks and “white” stocks is exactly this step. Brown stocks involve a roasting step that yields fuller, roasty flavors but which might mask more-delicate notes, depending on the animal from which you’re making your stock.

After completing all three stocks, I offered them to Sarah to taste. The MC pressure-cooked stock was robust and tasty. Interestingly, the MC non-pressure-cooked one tasted very similar, but didn’t have quite the depth of the pressure-cooked version. And the Alinea pressure-cooked version (a white stock) tasted anemic and watery by comparison, but with much brighter herbal notes. Surprisingly, none of them tasted anything like the veal stocks I’d made the traditional way from this cookbook previously, but they did all taste like stock you might find in a grocery store. It occurred to me later that this might be because Alinea does this two-step thing where they simmer the bones twice. I wonder (but haven’t yet tried) making the MC pressure-cooked stock from itself, fortifying it with two rounds of bones. I’m curious if this yields something closer to the rich, very full-bodied stock I’m used to.

The recipe here calls not only for veal stock, but also for goose stock. I’d be working with a whole goose over the course of making this dish, but had no idea how much a single goose’s bones weigh. Alinea’s traditional-approach recipe calls for 10 lbs of goose bones, onions, leeks, and various herbs to be cooked for around 6 hours. I suspected a single goose doesn’t pack around 10 lbs’ worth of bones, and (oddly) couldn’t find a butcher who could give me a decent estimate of how much the bones of a single goose was likely to weigh. After calling around for about a week, it seems as though most butchers don’t habitually carry goose, so tracking down that amount of bones proved unfruitful. One guy at Ver Brugge up in Berkeley asked if I could do with duck instead?

This sounded like an interesting contingency plan, so I said sure and placed an order for 10lbs of duck bones (and trimmings), and for a whole goose. The ingredient list for Modernist Cuisine’s duck stock almost-exactly matched that of Alinea’s (just the quantities of things differed), so I thought I had a good chance of landing pretty close to Alinea’s target by using Modernist Cuisine’s pressure-cooked approach. Interestingly, I noted that Alinea calls for roasting the bones for this stock.

While the duck stock was cooking, I worked on taking apart the whole goose itself. I saved all the bones and trimmings from it, roasted them, and (when the duck stock had finished), made another batch with the goose bones. Turns out that, because it’s more economical, using the pressure-cooked approach for the goose stock for this dish yields an amount that’s plenty for the needs of the dish…I didn’t need to make the duck stock at all. I’m pretty ok with this though…my freezer’s looking pretty respectable with the results of all this stock experimentation in it.

Another tricky goose component used frequently throughout this recipe is goose fat. Again, I had no idea how much fat a single goose yields, so as I was taking apart the whole goose, I was very conservative about hanging onto every scrap of fat I found. Goose butts are incredibly fatty, it turns out; I pulled a couple big wads the size of softballs out of the cavity of my goose and threw them and all my other trimmings in a pot with some water. My aim was to simmer this gently for a few hours in a process called “wet rendering”; fat melts and leaks out of the trimmings and floats on top of the water, where it stays cool and retains more of its natural flavor than with the more-violent dry-rendering technique of frying everything in a pan at much higher temperatures.

You can see in the above image the trimmings appear to be sitting on the bottom of the pan. They’re actually floating at the top of a water layer that’s sitting under a deep layer of fat that’s rendered out of the trimmings. After a few hours I let the mixture cool, strained it, then put it in the fridge overnight. The water and fat separate, the fat solidifying on top of the water. I poked a hole in it and drained out the water, melted the fat slightly, then poured it into jars. For anyone who might need this experience as reference, there’s plenty of fat in a single goose to do this recipe two or three times. Or, store it in your freezer along with all the rest of the stock you’ve made and tell your new wife it’s cool, you’ll find lots of ways to use this stuff.

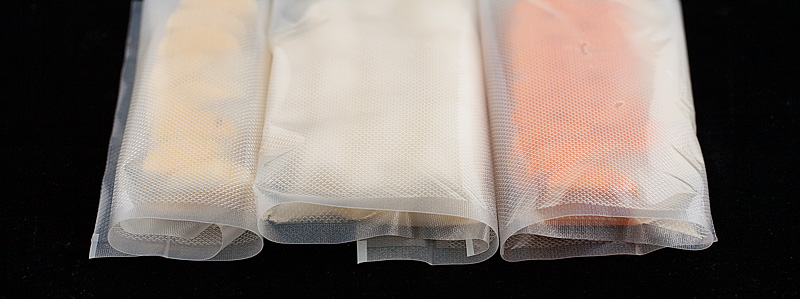

To make goose leg confit, the goose legs are cured overnight in a mixture of sugar, salt, a lot of orange peel, curing salt, nutmeg and other spices. They’re then cooked sous vide with some of the fat for several hours to render their collagen tender.

Conveniently, the temperature of the water bath for the confit legs is the same needed for that needed to make confit turnips and sweet potatoes, both of which were also packed in goose fat and dropped into a bath held steady by my new Nomiku.

And, simultaneously, I cooked some oranges with grapeseed oil and sugar in the same bath until the rind was very tender. This was then pureed with orange juice to yield Orange Sauce.

The skin of the goose legs is pulled carefully in big pieces, then the meat is removed from the bone and mixed with bread, cooked onions, leeks, fennel, celery seed, eggs, and goose stock to form a stuffing mix. The skin is placed in the bottom of a pan and the stuffing is packed on top, then the mixture is cooked until it’s springy. It’s then meant to be stored in the fridge overnight to firm up…under a 10lb weight (the reason for the weight is not given). Sarah barely batted an eyelash when she opened the fridge the following morning to find this:

The stuffing is cut into planks, then flipped skin side up and seared under a broiler to crisp the skin and warm it through just before service. The size of the planks and overall construction of them as dictated by the recipe is uncharacteristically rustic for Alinea, and were I to do it all over again I might make some changes: the vegetables in the stuffing are deliberately cut into a fine dice, but the goose leg meat is meant to remain in pieces “as large as possible”, which gives rise to big pockets in the stuffing and a really chunky texture. This made it hard to keep things tidy when cutting the planks. The portion dictated (1.5″ x 6″) is also maybe twice as wide as what the photo in the book appears to be, leading to the very rare case of this dish actually being pretty filling on it’s own.

The breast of the goose might have been one of my favorite things to make, mostly because I had no idea where I was headed with it when I started. The breasts were cured in another mixture of salt, sugar and spices, then packed in fat and cooked to medium-rare sous vide…then frozen. The recipe then says to remove the breasts and “remove excess skin”. Because I’d read ahead and was a little paranoid about how much goose fat I’d need (which I shouldn’t have been), I interpreted this as “remove the skin completely”, and so I figured why not do that before curing, and render the fat from the skin separately?

It was only as I was cooking the breast skin that I reread the recipe and realized I probably wasn’t meant to have done this. Hm. I wondered if there was a clever way to try to salvage this. I’d recently read about how to make chicharrones, or pork cracklings, which is puffed pork belly skin. The idea is simple: cook the shit out of the skin to rid it of fat, dehydrate it until it’s firm, then deep fry it until it puffs. The cooking step renders collagen to gelatin, which then traps residual water as it steams when the skin is fried, causing it to puff. I figured if fatty pork belly behaved this way, maybe my duck breast would? I cooked it at 190F for about 4 hours, then strained it and dehydrated it overnight. I noticed in the morning it still was leaking a fair bit of oil, so I scored it in a crosshatch pattern to see fi that might help it drain faster. After a couple hours, I pulled them from the dehydrator and tried dropping them in hot oil.

They crisped handily, but didn’t really puff the way I wanted. Maybe there wasn’t enough water in them? Maybe poultry skin doesn’t have the gelatin content pig skin does? They were kinda tasty, sort of like very crisp bacon, but not all the way magical (or maybe I think that because they didn’t work the way I envisioned).

At any rate, after this experiment I pulled my solid-frozen cured cooked goose breasts from the freezer. I was meant to slice it very thinly on a meat slicer, but because I don’t own one I just got my knife skillz on.

As the first paper-thin slice thawed, it dawned on me that I’d made sort of a prosciutto from these breasts. They had the same lovely texture and a salty spice taste that meshed perfectly with the flavor of the meat. This approach is again ostensibly streamlined for restaurant use, but the aim is obvious and the result is awesome.

Next up was cutting some foie gras from Hudson Valley into cubes, scoring them and searing them over high heat until meltingly tender and warm. Foie gras, the astute reader may note, is 100% illegal in California…to sell. Not being a restaurant though, I’m totally free to buy as much of it as I’d like, and out-of-state Hudson Valley is totally compliant with state law in shipping me some.

The final step in preparing the dish for plating was my favorite.

Into a bowl, I placed crushed nutmeg, blade mace, sage, thyme, and orange peel…all of which had been tossed in shiny melted goose fat.

At the same time, I warmed up some river rocks in my oven. I also broiled some of the stuffing planks, and re-thermed the turnip and sweet potatoes in a hot water bath. The veal stock was reduced and mixed with nutmeg to yield a dark, delicious Nutmeg Sauce, and it and the Orange Sauce were dotted onto a plate. When the stuffing planks came out of the oven, I quickly rolled slices of the Cured Goose Breast into cylinders and placed them on the plank, along with the foie gras, vegetables, and a supremed wedge of orange.

Then I removed one of the river rocks and placed it into the bowl of goose-fat-tossed aromatics.

The fat began sizzling immediately, and the room was filled with the aroma of a roasting goose, as if I’d opened the oven door on Christmas day. It smelled awesome.

Sarah and I sat down to enjoy the second Thanksgiving feast in one weekend (the first one involved smoking a turkey a la this awesome recipe). Amazing smell aside, the dish as a whole was pretty ok. There’s a lot of stuff to get on the plate all at once, and the temperature is critical…I had trouble keeping everything as warm as I’d have liked it. The unrefined texture of the stuffing was just ok for me; I couldn’t have picked out the flavors of the cured goose leg, just that there were giant chunks of meat in it. We both loved the goose prosciutto though, and the confit vegetables were a lovely texture.

Despite not being madly in love with the final result, I had a whole lot of fun making this one though. Crispy skin on top of stuffing is a sweet move that should find its way into regular stuffing recipes, and learning about stocks was great. I’ve also been on a jag to learn to cure my own meat (but that requires a cooler to age the meat in, and given our small apartment’s available space, I have to pick my battles), so getting a taste of that here was pretty rad.

This is one of those dishes I’ve been looking forward for you to make from the book and you did not disappoint. I recently shot a goose and might adapt the breast and legs to make a version of this.

Out of curiosity, how much did your whole goose cost? Like I’ve mentioned, I’d really like to roast a goose, in part to also have jars of creamy fat at my fingertips for months on end. (The recipe that I’ve been eying has you render fat out of the goose before roasting it–there is just too much fat to roast the goose straight off.)

Maybe you should have prepped that extra skin yakitori-style? I don’t know what that really involves, but there’s a Japanese small-plates place in Chicago that makes excellent crispy chicken skin.

Also, Modernist Cuisine looks super-awesome from the little excerpts you’ve been posting on Instagram. I would definitely like those volumes in my collection some day.

Fantastic blog and write up, great to see such dedication in the home kitchen, I look forward to reading more of your blogs.

As always, the attention to details leaves me speechless. The end result is absolutely stunning.

As one that I had to make several batches of the French Laundry veal stock, all I could say is I still have occasional nightmares about having to cook another batch :).

Is the bowl you used for aromatics made by Crucial Detail? It looks prey neat.